The Immigrant Church

French missionaries transplanted Catholicism from Western Europe to Wisconsin. French Jesuits and others instructed native peoples in the Catholic faith, challenging their existing religious beliefs while also building on points of similarity.

French missionaries transplanted Catholicism from Western Europe to Wisconsin. French Jesuits and others instructed native peoples in the Catholic faith, challenging their existing religious beliefs while also building on points of similarity.

French Catholicism had a short life in Wisconsin, mostly because the Jesuits were formally suppressed in 1760. French colonization of Wisconsin was never as intense as the Spanish or English settlement of their respective frontiers.

When Wisconsin came under the jurisdiction of the United States in 1783 and the territory was ordered and organized according to the principles of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, more white settlers moved into the territories around the Great Lakes. Native American claims to land were contested by war and by treaty.

Immigration Policies

For many years, the United States had no laws restricting anyone from entering the country. People from northern and western Europe migrated to the United States for various reasons, among them war, lack of economic opportunity, religious and legal persecution, and famine. Others came for family kinship ties or the prospect of land ownership on America’s expanding frontier. Improvements in trans-Atlantic travel facilitated immigration.

The Old Immigration: 1830-1890

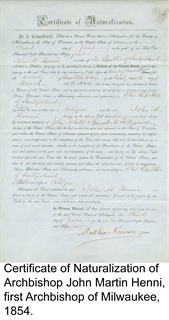

The first waves of immigrants coming into Wisconsin were the Irish and Germans.

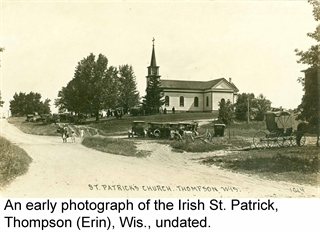

Irish miners came in the 1820s for the “lead rush” in southwestern Wisconsin. In the 1840s, the lure of Wisconsin land attracted a number of Irish who had already settled in the East, some escaping Ireland’s potato famine (1845-1850). By 1860 there were 50,000 Irish-born residents in Wisconsin. Irish numbers never “took off” as they would in other parts of the United States, but Irish enclaves in the state included Janesville, East Troy, and pockets in Milwaukee, Kenosha, Racine, and small farming communities.

Irish miners came in the 1820s for the “lead rush” in southwestern Wisconsin. In the 1840s, the lure of Wisconsin land attracted a number of Irish who had already settled in the East, some escaping Ireland’s potato famine (1845-1850). By 1860 there were 50,000 Irish-born residents in Wisconsin. Irish numbers never “took off” as they would in other parts of the United States, but Irish enclaves in the state included Janesville, East Troy, and pockets in Milwaukee, Kenosha, Racine, and small farming communities.

Irish Catholicism was influenced by a devotional revival in Ireland in 1850s, with an emphasis on Marian devotion (the rosary), novenas, and devotion to the Sacred Heart. Irish churches were simple and not overly-decorated.

German speakers migrated to Wisconsin in large numbers. In fact, Wisconsin had one of the largest concentrations of German speakers in the Midwest. Germany would not be unified into a single nation until the 1870s, so many different groups came. Many came from Northern Prussia (they were often Lutherans or evangelicals.) Southern Germans, Bavarians, and other tended to be Catholics as did the Austrians and many Swiss. German speakers also came from Luxembourg, Bohemia, and Lithuania.

German speakers migrated to Wisconsin in large numbers. In fact, Wisconsin had one of the largest concentrations of German speakers in the Midwest. Germany would not be unified into a single nation until the 1870s, so many different groups came. Many came from Northern Prussia (they were often Lutherans or evangelicals.) Southern Germans, Bavarians, and other tended to be Catholics as did the Austrians and many Swiss. German speakers also came from Luxembourg, Bohemia, and Lithuania.

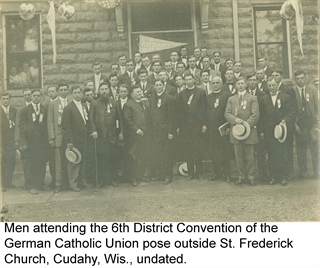

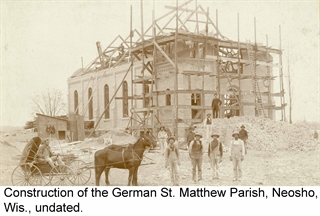

German immigration to Wisconsin accelerated in the 1850s. The State of Wisconsin created an office of emigration in 1852 and sent agents and literature to various areas of German-speaking Europe and German speakers living in the east to promote the possibilities of living in Wisconsin.  The numbers of German speakers increased dramatically between 1850 and 1870. German speaking enclaves could be found in most of Wisconsin’s cities. Germans were productive farmers and created networks of association, often using their churches as gathering points. Germans also settled in large cities such as Milwaukee, Madison, Racine, Kenosha, Sheboygan, Fond du Lac, and Beaver Dam. Here they brought skills in brewing and other forms of commerce, publishing, and politics.

The numbers of German speakers increased dramatically between 1850 and 1870. German speaking enclaves could be found in most of Wisconsin’s cities. Germans were productive farmers and created networks of association, often using their churches as gathering points. Germans also settled in large cities such as Milwaukee, Madison, Racine, Kenosha, Sheboygan, Fond du Lac, and Beaver Dam. Here they brought skills in brewing and other forms of commerce, publishing, and politics.

German Catholics played a prominent and decisive role in the shaping of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. The first four Milwaukee bishops were German speakers. St. Francis de Sales seminary was founded, in part, to educate German-speaking seminarians.  The Germans built architecturally prominent and distinct churches, and German sisterhoods (the School Sisters of Notre Dame, the School Sisters of St. Francis, the Franciscan Sisters of Penance and Charity, the Wheaton Franciscans, the Sisters of the Divine Savior, and the Racine Dominicans) created Catholic schools, hospitals, and protective institutions. German Catholic parishes had numerous societies for different age groups and genders. They sustained a very popular local newspaper, Seebote, and marched in elaborate parades with banners and musical accompaniment to celebrate religious holidays and festivals. German-language instruction was common in German Catholic schools and German sermons were the rule in parishes until World War I.

The Germans built architecturally prominent and distinct churches, and German sisterhoods (the School Sisters of Notre Dame, the School Sisters of St. Francis, the Franciscan Sisters of Penance and Charity, the Wheaton Franciscans, the Sisters of the Divine Savior, and the Racine Dominicans) created Catholic schools, hospitals, and protective institutions. German Catholic parishes had numerous societies for different age groups and genders. They sustained a very popular local newspaper, Seebote, and marched in elaborate parades with banners and musical accompaniment to celebrate religious holidays and festivals. German-language instruction was common in German Catholic schools and German sermons were the rule in parishes until World War I.

Milwaukee was the center of a significant controversy among prelates of the Catholic Church over the issue of language. Some bishops and priests argued that foreign languages should give way to English and a fuller embrace of the American way of life. Other prelates, Milwaukee’s archbishops and priests among them, insisted on the preservation of German language and culture as the way to preserve the faith. Within the presbyterate of the archdiocese, priests took opposing views on this: English-speaking clerics wanted a more “American” diocese and urged the appointment of an English-speaking archbishop. German clerics and sisters insisted on the perpetuation of German language and culture. Eventually the disagreement found its way to Rome and Pope Leo XIII condemned “Americanism” in 1899, a seeming vindication of the position of Milwaukee’s archbishops.

The New Immigration: 1880-1924

Beginning in the 1860s and extending into the 20th century, Wisconsin’s economy transitioned to manufacturing. Foundries, forges, factories of various sorts, and commercial shipping (land and lake) became a central feature of this new economy. Industrial workers, many from southern and central Europe as well as African Americans from the Deep South, came to work in these industries or service industries.

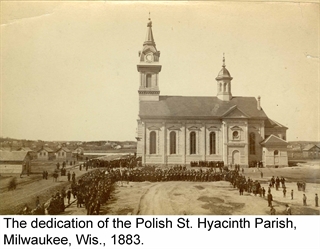

Poles began coming in the 1860s. Many of them came from Prussian Poland and other Polish-speaking areas of Europe (Poland had been dismembered as a nation but reassembled in 1918). Poles lived on Jones Island (Kazubes) and also in manufacturing cities of Milwaukee, Racine, and Sheboygan. In each city, they created their own urban enclaves where they kept language and culture alive through social and cultural institutions and the churches. The oldest Polish church in Milwaukee, St. Stanislaus, opened in 1866. Polish Catholics were quick to form schools and a local press. Virtually every industrial town of any size had at least one Polish parish. Perhaps the most stunning example of the Polish Catholic presence was the erection of St. Josaphat Basilica on the south side of Milwaukee.

Poles began coming in the 1860s. Many of them came from Prussian Poland and other Polish-speaking areas of Europe (Poland had been dismembered as a nation but reassembled in 1918). Poles lived on Jones Island (Kazubes) and also in manufacturing cities of Milwaukee, Racine, and Sheboygan. In each city, they created their own urban enclaves where they kept language and culture alive through social and cultural institutions and the churches. The oldest Polish church in Milwaukee, St. Stanislaus, opened in 1866. Polish Catholics were quick to form schools and a local press. Virtually every industrial town of any size had at least one Polish parish. Perhaps the most stunning example of the Polish Catholic presence was the erection of St. Josaphat Basilica on the south side of Milwaukee.

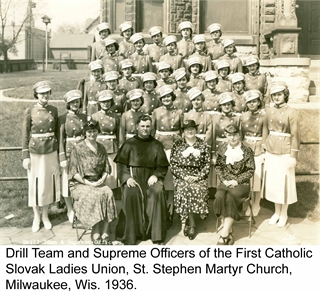

Italians, Hungarians, Slovaks, and Lithuanians followed suit. They worked in factories or service industries (barbers, grocers, retail). Each of them created their own communities in cities. Kenosha, for example, had a very significant concentration of southern Italians from the Province of Cosenza. Churches and devotional societies, as well as religiously themed festivals became an important part of Catholic life for these groups.

Italians, Hungarians, Slovaks, and Lithuanians followed suit. They worked in factories or service industries (barbers, grocers, retail). Each of them created their own communities in cities. Kenosha, for example, had a very significant concentration of southern Italians from the Province of Cosenza. Churches and devotional societies, as well as religiously themed festivals became an important part of Catholic life for these groups.

Among all of these immigrants, old and new, priests sometimes functioned as community leaders and advocates. For example, the Polish respected Father Wenceslaus Kruszka, whose half-brother Michael also produced a popular Polish-language newspaper, Kuryer Polski

Catholics of various ethnicities lived in proximity to each other and worked together, but kept a distance from each other when it came to having their own worship space, often in close proximity to a rival nationality. For example, Old St. Mary’s Church, founded in 1846 for Germans, was only two blocks away from St. John’s Cathedral, which was dominated by the Irish.

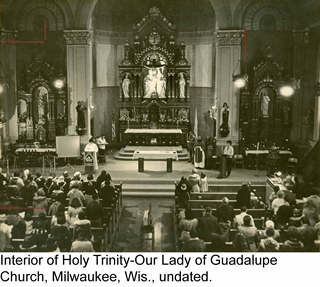

Mexicans came in different periods, some settling on the Southside of Milwaukee. Many worked as migrant laborers on Wisconsin farms. Catholic outreach to them was handled by various groups, including the Redemptorists, who had a center in Oconomowoc. A chapel for the Spanish-speaking, Our Lady of Guadalupe, was founded in the 1920s on the Southside of Milwaukee. Later, waves of Latino immigrants came through the “Bracero Program” of the 1940s. The help of Mexican laborers in maintaining the production of food during World War II and beyond was important. Mexican immigration was curtailed in the 1950s, but resumed in the 1980s. Spanish speaking workers served as farm laborers, meat-packers, and in service jobs. The archdiocese created an outreach to Mexicans in the 1960s through sacramental ministry, education, and social service centers (The Spanish Center, Milwaukee.) Puerto Ricans and Cubans also came to Milwaukee in the 1950s.

Mexicans came in different periods, some settling on the Southside of Milwaukee. Many worked as migrant laborers on Wisconsin farms. Catholic outreach to them was handled by various groups, including the Redemptorists, who had a center in Oconomowoc. A chapel for the Spanish-speaking, Our Lady of Guadalupe, was founded in the 1920s on the Southside of Milwaukee. Later, waves of Latino immigrants came through the “Bracero Program” of the 1940s. The help of Mexican laborers in maintaining the production of food during World War II and beyond was important. Mexican immigration was curtailed in the 1950s, but resumed in the 1980s. Spanish speaking workers served as farm laborers, meat-packers, and in service jobs. The archdiocese created an outreach to Mexicans in the 1960s through sacramental ministry, education, and social service centers (The Spanish Center, Milwaukee.) Puerto Ricans and Cubans also came to Milwaukee in the 1950s.

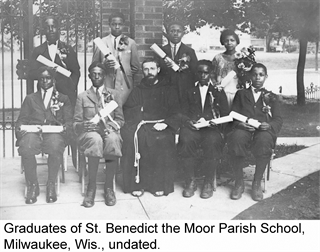

African Americans came to the Midwest in large numbers, fleeing Jim Crow in the South and seeking industrial and service jobs in the North. Milwaukee and Racine’s African-American communities grew slowly in the 20th century. In 1908, an African-American couple, Lincoln and Julia Valle, established a mission to African Americans, St. Benedict the Moor Church. It was later taken over by the Capuchins, aided by the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the Racine Dominicans, who opened a day and boarding school for these children. After World War II, the African-American population of southwest Wisconsin (mostly Racine and Milwaukee) grew significantly. African-American Catholics joined existing parishes mostly on Milwaukee’s north side. Sometimes they met resistance. In other places, there were efforts to maintain integrated parishes.

African Americans came to the Midwest in large numbers, fleeing Jim Crow in the South and seeking industrial and service jobs in the North. Milwaukee and Racine’s African-American communities grew slowly in the 20th century. In 1908, an African-American couple, Lincoln and Julia Valle, established a mission to African Americans, St. Benedict the Moor Church. It was later taken over by the Capuchins, aided by the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the Racine Dominicans, who opened a day and boarding school for these children. After World War II, the African-American population of southwest Wisconsin (mostly Racine and Milwaukee) grew significantly. African-American Catholics joined existing parishes mostly on Milwaukee’s north side. Sometimes they met resistance. In other places, there were efforts to maintain integrated parishes.

Anti-Catholicism

Immigrants Catholics sometimes prompted xenophobic reactions in Wisconsin and around the country. In Wisconsin, German liberals of the 19th century variety took a dim view of the Church as a reactionary organization. Forty-eighters (anti-clerical reformers from the German revolution of 1848) encouraged anti-Catholic invective in the local press, harassed religious sisters, and suggested that Catholics could not be loyal citizens.

More serious anti-immigrant bias, focused around anti-Catholicism, emerged in the 1840s and 1850s through the nativist movement and the Know-Nothing Party (an anti-Catholic political party of the 1850s). These elements openly despised Catholic participation in public life, teaching, and journalism. In their minds, being a Catholic disqualified a person from being a good American.

The American Protective Association, an anti-Catholic group founded in Clinton, Iowa in 1887, was concerned about Catholic influence in public life and schools. This group attempted to restrict Catholic participation in law enforcement, politics, and teaching.

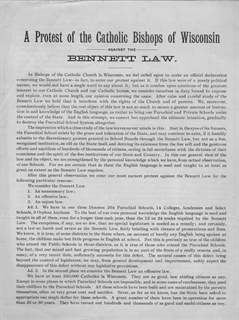

In Wisconsin, the 1889 Bennet Law required the use of English in public and private schools to teach major subjects. German Catholics and Lutherans who had schools reacted negatively to this. It was also deemed an attack on Catholic schools in general. Archbishop Frederick Katzer and other clergy loudly denounced this law. English-speaking Catholics were initially unsure, but when the law’s advocates grew were so anti-Catholic they joined with Germans to oust the governor and legislators who supported the law. The law was repealed in 1891.

In Wisconsin, the 1889 Bennet Law required the use of English in public and private schools to teach major subjects. German Catholics and Lutherans who had schools reacted negatively to this. It was also deemed an attack on Catholic schools in general. Archbishop Frederick Katzer and other clergy loudly denounced this law. English-speaking Catholics were initially unsure, but when the law’s advocates grew were so anti-Catholic they joined with Germans to oust the governor and legislators who supported the law. The law was repealed in 1891.

In the 1920s, a second version of the Ku Klux Klan emerged, similar to the post-Civil War terrorist organization that had arisen in the South. This first Klan targeted African Americans who dared to vote or who insisted on social equality with whites. This organization (but not its ideas) was put out of business by the U.S. government. A second Klan began in 1915 and encouraged suspicion and fear of immigrants, domestic subversion by communists, and resistance to Prohibition. Wisconsin had about 15,000 Klan members, heavily concentrated in Milwaukee and Madison.

This group continued its hatred of people of color, but also targeted Catholics as disloyal and incapable of being “100 percent American.” Catholicism was seen as a deterrent to personal independence and freedom. Catholics were “priest ridden” and subject to autocratic leadership, traits not compatible with citizenship in a democratic republic. The Klan flourished through the twenties, but by 1928 faded away in Wisconsin.

Immigration Policy: 1921-1924

Efforts to restrict immigration to the United States began with laws banning the Chinese from entering.

In the early 20th century, a considerable body of pseudo-scientific thought on the differences in race was brought to bear on the issue of immigration. The nation was being flooded with millions of immigrants every year, many of them passing through Ellis Island, a checkpoint in New York harbor begun in 1892. Eventually this pseudo-science, endorsed by many Wisconsin academics and politicians, determined that people of northern and western European ancestry were the best disposed to come to the United States. Those from southern and eastern Europe, Latin America, or other southern latitudes were considered racially inferior and unfit to mix with white Americans. In the mind of some, these immigrants “disability” included their Catholic faith

Efforts to restrict immigrants were advanced in Congress in the early 20th century—excluding certain classes of people (among them, the mentally ill, anarchists, and those with contagious diseases.) In 1921, Congress halted the number of immigrants coming from “inferior” places, and in 1924 the Johnson Act placed strict immigration quotas based on nationality. This radically restricted the number of southern and eastern Europeans allowed to come to America. This attitude toward foreigners was advanced by groups like the Klan. Aligned with this movement was a noticeable Eugenics Movement, which reinforced spurious ideas about racial purity and sought to eliminate undesirables by excluding them from America. These ideas were very popular with academics and many in public service and sometimes included suspicion of Catholics.

The impact of these attitudes on the Catholic Church was cutting off new immigrants from existing ethnic communities who had established themselves throughout the state. It encouraged “Americanization” through the use of English in parishes and schools. Intermarriage between members of ethnic groups created a mixed nationality, further promoting Americanization. The racist underpinning of these policies became embarrassing after the United States battled the hideous policies of Hitler’s Third Reich in World War II.

In 1952, Congress passed further restrictive legislation, the McCarran-Walter Act, over the veto of President Harry Truman.

Immigration Reform: 1965

Beginning in 1965, revision of existing immigration laws re-oriented American immigration policy. It did away with the national origins system set up by the laws of the 1920s and 1952. The new law (the Hart-Celler Act) included refugees and also encouraged chain migration from Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. At the same, time political upheavals resulting from the Vietnam War brought many refugees and other immigrants to the United States and Wisconsin.

One large group that made Wisconsin its destination was the Hmong. After the fall of Saigon and Laos in 1975, Hmong began to flee to the United States. From the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, thousands of Hmong refugees resettled in the United States. Wisconsin cities with large Hmong communities included Milwaukee, Racine, and Sheboygan. Vietnamese Catholics, fleeing the persecution of the North Vietnamese government, also were welcomed in large numbers to the US. The archdiocese facilitated social and services and ministerial outreach to them.

New Immigration

The waves of new immigrants coming from Mexico, the Pacific Islands, and Asia have made their presence felt through parish life. Various parishes in the archdiocese have created spaces for worship, cultural expression, celebration of holidays, and provided social services. The concerns of Spanish speakers have found significant support through archdiocesan planning, educational outreach, and the recruitment of priests and religious to minister to these communities. Parishes in various parts of the diocese that had once been the domain of earlier ethic groups have now become important centers of Hispanic evangelization and education.

The waves of new immigrants coming from Mexico, the Pacific Islands, and Asia have made their presence felt through parish life. Various parishes in the archdiocese have created spaces for worship, cultural expression, celebration of holidays, and provided social services. The concerns of Spanish speakers have found significant support through archdiocesan planning, educational outreach, and the recruitment of priests and religious to minister to these communities. Parishes in various parts of the diocese that had once been the domain of earlier ethic groups have now become important centers of Hispanic evangelization and education.

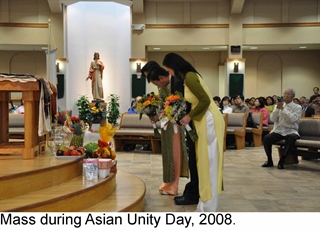

Pacific Islander and Asian Catholics have also found church homes in Milwaukee, Sheboygan, and elsewhere. Efforts to draw attention to these groups are highlighted in archdiocesan communications and through the ministry of lay persons, priests, deacons, and religious.

By Rev. Steven Avella

Photographs and documents courtesy of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Archives, unless otherwise noted. Photographs and documents cannot be reproduced without prior written authorization. For permission to reproduce contact the archdiocesan archives.